Thalia Kattoura | Senior Editor of Identity

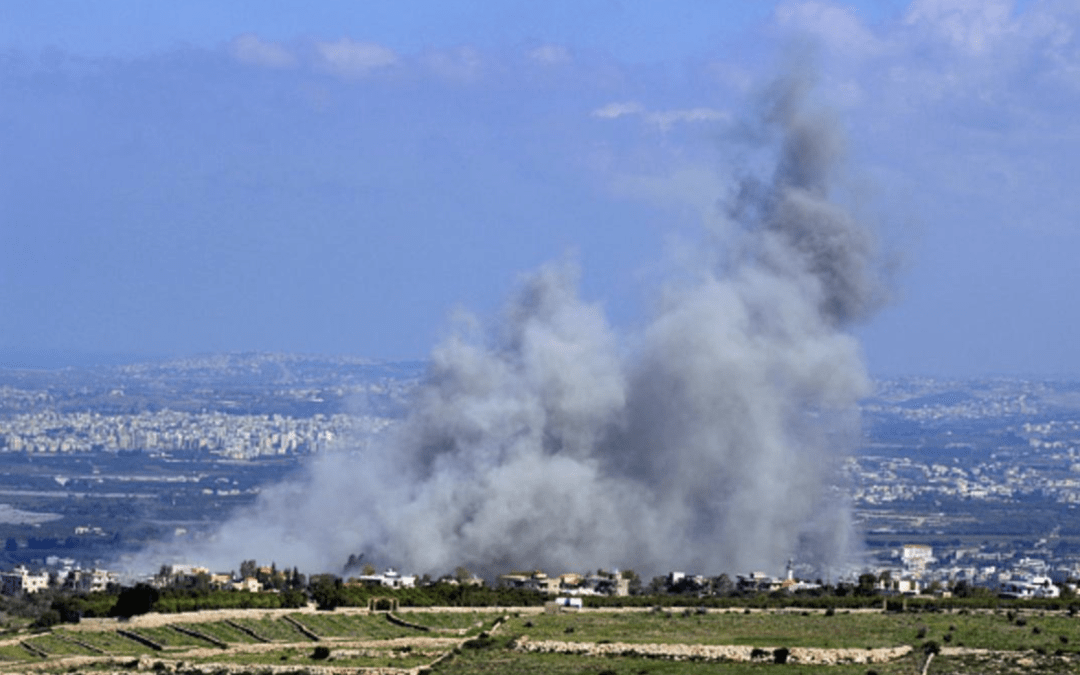

Amidst the escalating Israeli aggression in Palestine and its attacks on rural areas in Lebanon, particularly in the south, a slogan is gaining traction across the nation: “جنوب لبنان جزء لا يتجزأ من لبنان” (South Lebanon is an integral part of Lebanon).

In shedding light on Lebanon’s peripheries, where political isolation from Beirut casts a shadow over daily life, we uncover a narrative of resilience amidst neglect. As we trace the timeline of the Israeli occupation and examine the particular case of white phosphorus munitions, it becomes clear that the impact of external aggression extends far beyond physical destruction. From crumbling infrastructure to dwindling opportunities, residents of Lebanon’s peripheries face a multitude of challenges as they navigate a world apart from the economic and political center of Beirut.

Rough Timeline of the Israeli Occupation on Lebanese Grounds

“We have to establish a buffer zone in Lebanon as it is clear that the Lebanese government will do nothing to stop terrorism. The establishment of such a zone will obviously mean the annexation part of Lebanese territory.” – Ariel Sharon, 1981.

During Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948, Lebanese border villages were occupied, displacing their residents alongside Palestinian villages. Although some villages were returned with the signing of the Lebanese-Israeli armistice agreement in 1949, many suffered destruction, including historic and cultural sites.

The Israeli invasions of South Lebanon in the 1980s left a lasting imprint on the region, with repercussions still felt today. Israel quickly asserted control over the area through military governors and extensive bureaucratic measures. This included gathering detailed information about the population, surpassing even the Lebanese government’s knowledge. Moreover, Israel sought to integrate South Lebanon into its economy, emphasizing trade links and the free movement of goods and individuals. However, this integration was largely one-sided, with Israel benefiting economically while imposing its influence on the region. For instance, significant quantities of produce, including strawberries, grapes, mangoes, and apricots, flowed from Israel into South Lebanon, highlighting the economic disparity and asymmetry of power.

The 2006 war resulted in the displacement of about one million Lebanese residents, severe damage to infrastructure, and loss of civilian lives.

Since October 8, 2023, over 82,000 people, including many children, have been displaced due to Israeli aggression on Lebanon. The number of displaced doubled within a week in November and saw another substantial increase from early December to early January. Most displaced individuals come from three districts along Lebanon’s southern border with occupied Palestine. They have been forcibly displaced to eight districts across the country, with Sour receiving the largest number of displaced individuals.

The agricultural sector in southern Lebanon has been severely affected by the conflict, with significant damage to fruit, olive, and citrus farms. The use of white phosphorus by Israel has exacerbated the destruction of agricultural areas, causing fires and extensive economic losses.

Furthermore, 91 villages have been targeted by cross-border attacks, leading to the destruction of dozens of buildings and disruption of infrastructure and social services. Aita al-Shaab, Yaroun, and Mais al-Jabal have been the most targeted villages.

In Lebanon, the absence of the state in the south has profound implications for the desensitization of people in the region. Historically, the southern areas of Lebanon have experienced limited government presence and investment, particularly compared to the capital city, Beirut, and other urban centers. This lack of state attention has resulted in inadequate infrastructure, limited access to basic services like healthcare and education, and economic underdevelopment.

The Particular Case of White Phosphorus

Exposure to white phosphorus (WP) munitions can lead to reduced productivity of agricultural land, with existing plants susceptible to adverse effects such as desiccation, dieback, and wilting. Additionally, WP shelling may ignite extensive fires that spread over large areas and persist until the material is fully depleted. Comprehensive research, complemented by on-site data collection, is necessary to assess the severity of these hazards. In Lebanon and the wider region, the use of these incendiary weapons is detrimental to forest ecosystems and their endemic biodiversity.

The National Council for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Lebanon has documented the intensity of fires in South Lebanon. Between October and November 2023, approximately 462 hectares of forests and agricultural fields were completely ravaged, partly due to WP. The infiltration of WP into soil poses a threat to various living organisms, especially when it reaches rivers and aquifers, potentially impacting populations reliant on these water sources. The subsequent effects include contamination of agricultural land and water streams, posing risks to crops, cattle, and nearby communities.

Moreover, WP contamination can jeopardize food security and local economies, as it affects ecosystems and fisheries. The long-term presence of toxic residues necessitates costly decontamination processes to safeguard communities and the environment. In addition to the immediate physical destruction caused by WP shells, fires resulting from their use damage houses, commercial units, vehicles, and agricultural land, leading to significant financial losses for affected citizens.

During the same period, the IDF raids destroyed over 40,000 ancient olive trees, partly through the use of WP. These trees are vital for local communities, providing essential income and serving as cultural and heritage symbols. Furthermore, the use of WP munitions contributes to the internal displacement of tens of thousands of inhabitants, disrupting livelihoods, education, healthcare, and mobility at both local and national levels. Overall, WP munitions have far-reaching implications for regional social and economic stability, exacerbating inequalities and undermining wellbeing.

Mr. Abousari expressed his fear that his 5500-square-meter plot of land would become unusable. He lamented the destruction of his sprinkler system by bombs, estimating his losses at least $4,000. “If your land is sick, you can’t work anymore. What will you do?” he questioned, highlighting the region’s reliance on daily wages and the uncertainty surrounding his future livelihood. Desperate for answers, he initiated soil testing in collaboration with an association to determine if the land was contaminated, anxiously awaiting the results. “We want to know what we are going to do; this is a project of my life,” he emphasized, underscoring the significance of his land for sustaining himself and his son’s future.

Conclusion

The narrative of Lebanon’s peripheries is one of resilience in the face of adversity. Despite enduring the brunt of external aggression and political isolation from Beirut, communities in the south persist in their pursuit of livelihoods and dignity. From the scars of Israeli invasions to the environmental devastation wrought by white phosphorus munitions, the challenges they face are manifold. Yet, amidst crumbling infrastructure and limited opportunities, there exists a spirit of resilience that refuses to be extinguished. As we reflect on the stories of individuals like Mr. Abousari, who cling to their land and livelihoods despite the odds, we are reminded of the indomitable human spirit that prevails even in the darkest of times. Moving forward, it is imperative that Lebanon’s peripheries receive the attention and support they deserve, for their struggles are not just a reflection of their own resilience, but also a testament to the broader issues of inequality and neglect that plague society as a whole.

I will conclude with the anecdotes of civilians from the South of Lebanon, extracted from Reuters Reporting:

“The war is being waged at the border. Maybe it’s not our turn yet but you don’t know what will happen in a few days. You just wait,” said Rabab Yousef, a 57-year-old mother who lost a daughter under the rubble of an Israeli airstrike in 2006.

“Every once in a while, they create a war and one loses a family member. You give birth to a child and you don’t know whether this child will stay with you,” she said.

“It’s in front of me as it happened today. Especially the children, nothing breaks your heart like children (being killed),” said Jamil Salameh, 56, a survivor of the attack and now a security guard at a monument to the 1996 incident.

Sabah Krecht, aged 57, expressed concerns about the ongoing conflict in Lebanon, emphasizing the deep economic crisis that has made it financially difficult for many people to leave. Despite feeling afraid and recognizing the possibility of fleeing, she highlighted the financial constraints faced by individuals like herself, making it challenging to seek refuge elsewhere.

Sources:

https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1363529/100-days-of-conflict-in-southern-lebanon-key-facts.html

https://www.newarab.com/news/situation-displaced-south-lebanon-unsustainable

https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/people-southern-lebanon-rushing-home-amid-truce-hope-fighting-is-over-2023-11-29/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3991719

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41145990

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/14/whats-behind-israels-escalation-on-south-lebanon

https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/south-lebanon-town-border-conflict-brings-fear-resignation-2023-10-25/

https://www.aub.edu.lb/natureconservation/Documents/Brief%20WP%20English.pdf

https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/lebanon/2023/11/28/lebanon-white-phosphorus-dhayra-truce/