By Nour Al Houda Jaafar Atieh | Staff Writer

Slow down for once.

And, look up.

Now, look around you.

We are surrounded by stories, but we refuse to listen. We are surrounded by art, but we refuse to look. Promise me that the next time you are walking on Hamra street, you will take a minute and take everything in. We are in an art gallery.

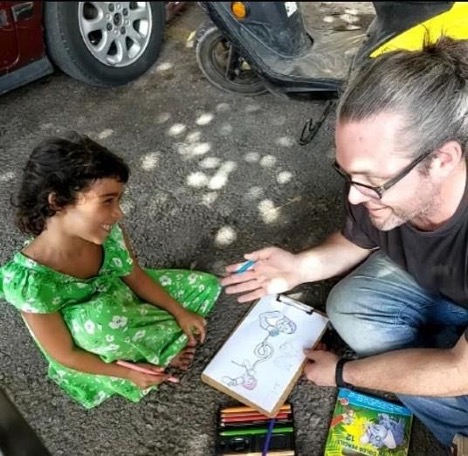

A man sits on the sidewalk in Hamra with half a dozen kids around him; they are all drawing on papers and fighting over who gets the red colored pencil. They fight and plead, “Ammo Fanan, I want you to paint me on this wall, and I want the color blue in it.”

Ammo Fanan obliges. A man that dedicated his time, craft, and life to those people, whom are never seen nor heard because he wants them to know that they are important.

Brady Black, Ammo Fanan, started his street art journey last year in October when the owner of Art of Change suggested that he should try it, and since then, Ammo Fanan never stopped.

I ask him, “Why street art?”

“Why not? We are surrounded by advertisements. Public space belongs to the people, yet we have no choice of what is displayed in it,” he replied with utmost focus, for he didn’t stutter nor lose track as if he already knew that I would ask him this question.

Instead of the invasive advertisements that you wish to unsee, you could have art. You have both. An artist sketches, selects color, and chooses a canvas, and in the end, he doesn’t get paid because in most cases it is considered an act of vandalism.

An act of vandalism that sheds light on people who are often left out and even hated. An act of vandalism that tells a story. An act of vandalism that asks you to think. An act of vandalism that is the voice of the people.

However, according to Black, he sets a boundary for himself that is a line, he will never cross. Art, especially street art, can be used as a tool to talk about politics, yet Black believes that he does not have a say in this because it is not his country.

“I am a foreigner,” he says.

According to Black, technically, he is not Lebanese, yet he stands on their side. During his stand in the revolution, he went down and sketched what caught his eye, but he was called a spy. He laughs and speaks of the Lebanese people and their conspiracy theories, “I am an American spy trying to gather information on the people.”

We laugh about it, and I tell him, “I think it is the best cover there is. An American spy disguised as a street artist blending with the people and hearing everything.”

Every spy should know his environment and its unspoken rules. Even a big man like Black avoids certain places because, according to him, street art tells you where you are welcomed or not. The American spy adopted his own navigation system through cans of paint and scribbles on walls.

Street art is already dangerous by itself, and if you are a woman, it is already more difficult. A street artist walks the streets at night and comes across many people along their way, which means that it is an art that is restricted by gender. An art restricted to certain gender, men, not because it is classified as such, but because of the environment, safety, and society that make it restrictive. However, Black had mentioned that he invites female artists to explore the city to find a good spot for their art.

“Why do people not like certain street art?”

Black had started a series of posts on his stories on Instagram asking his followers to choose between a blank wall and one with scribbles on it. The majority chose a blank wall, but they also added that they don’t mind a beautiful art piece.

“Well, I like everything. I want to know that Fadi loves Mariam. I want to know Kareem was here,” he was excited as the corners of his mouth tugged on a smile.

What is art?

Black accepts all street art from murals to a simple love equation; he loves them because those scribbles let you know that that youth is present. He challenges us to think about our definition of art. What is art? What is beautiful? What should be seen and heard? What shouldn’t?

“Your art will be ruined,” I told him because it is something we expect. It will either fade away, be torn apart, covered, or drawn over.

“I don’t expect it to last forever. Besides, it is part of the graffiti conversation,” he replies.

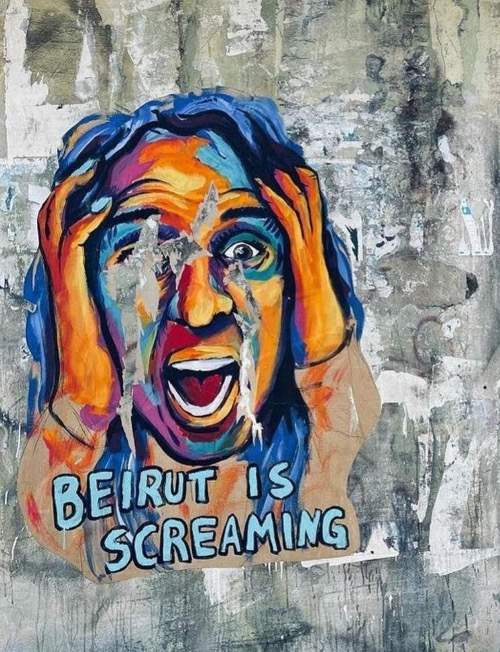

Black knows that what he is doing is illegal and considered an act of vandalism, so he does not mind when someone ruins his art. He adds that tearing his art is part of the discussion such that one of his pieces, “Beirut is screaming” was messed with and torn, but he thought it looked better this way because the painting was now part of the city and its people.

“It is a good thing to offend someone with my art”, he adds.

Art is a conversation because it all depends on the audience, their perspective, their thinking, and their background. So, if someone chooses to mess up Black’s work, he enjoys it; it is all summed up in one conversation.

One of the most known pieces of his is the memorial of the victims of the deadly August 4 port blast with a series of 204 portraits of those killed by the explosion. He tells me that it was done with cheap material like glue and golden spray instead of a golden frame; it is a critique, he says. It is a conversation, he says.

Someone called to tell him that the memorial is deteriorating, and some photos have faded away. “I will do nothing. It is yours to do,” he speaks.

It should offend you. It should make you mad. 204 souls were lost 458 days ago. No justice. No explanation.

It is a critique of us, in a way. We are letting those faces deteriorate. We are letting this happen to them. After 458 days, we stand without justice. After 458 days, we have numbed the pain. After 458 days, we have forgotten about them. After 458 days, we remain silent.

I asked him for advice, but he was unsure because it is not his battle to have a say. I demand from the foreigner whose face is on my laptop screen: “What do you see that we don’t see? What do you see in this world of ours? What do you see in these people?”

“Resilience,” he says, “and not in a good way.”

He has hope for us. He believes that we are just like a cedar tree. Strong. Resilient. Broken.

He ended the meeting with a statement, “Stop being resilient. Stop allowing crappy things to happen and keep fighting to fix things.”

“And, make more art.”