Game of Corruption

Vol. XXII, No. 1, 2024

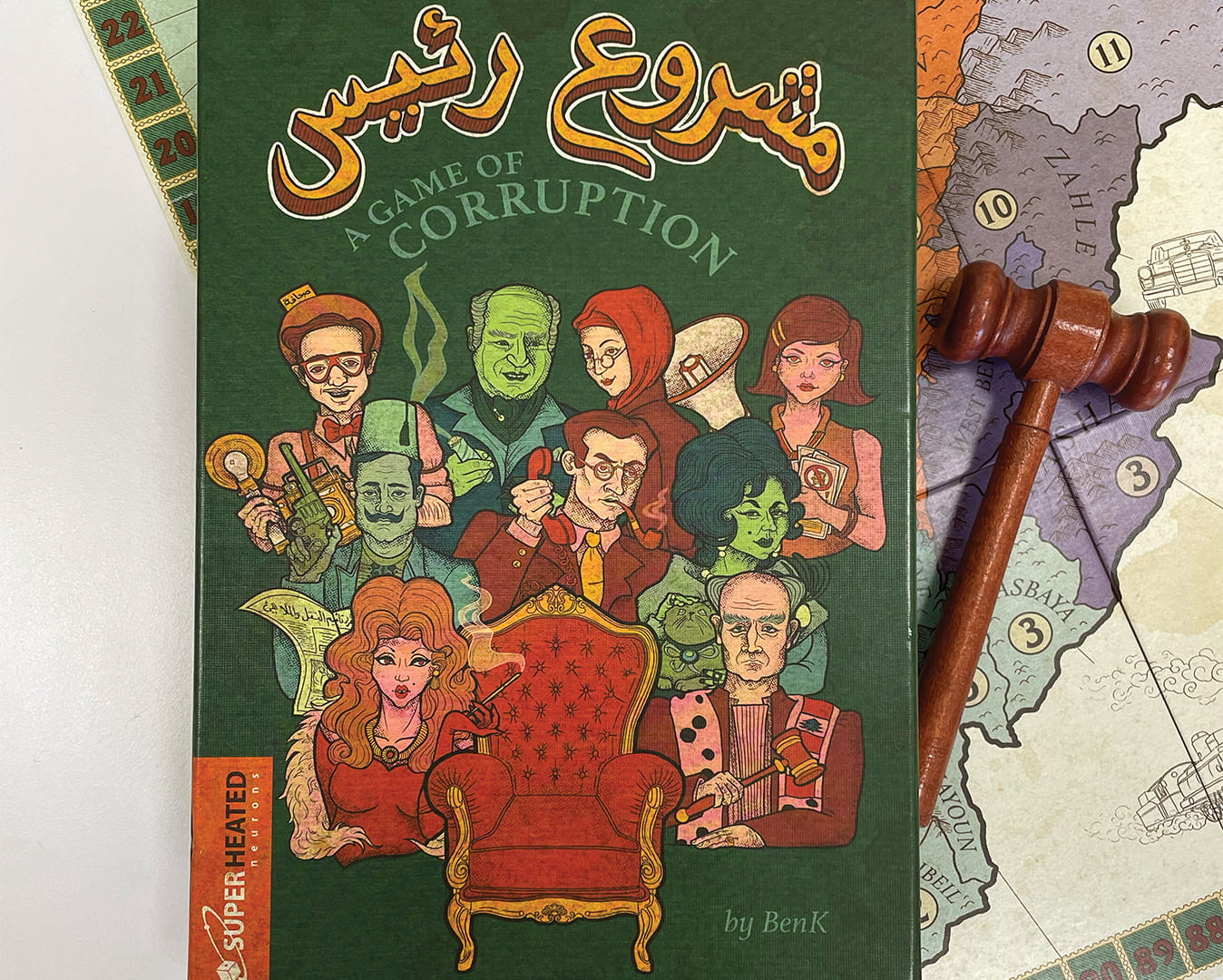

Kellon ya3ni kellon!” The chant rang out in Lebanon’s squares and was reprinted on newspapers in the wake of the 2019 protests. It was a call for the total abolition of Lebanon’s political class; no one could be spared because no one could be trusted. And yet politicians across the political spectrum, young and old, joined in, sounding a similar note: corruption must end, change must occur, we are with the movement. To parse fraud from forthrightness amidst the political maelstrom was impossible, which is exactly the point of the new board game Machrou3 Ra2is: A Game of Corruption, designed and published by AUB alumnus Jean Michel Chemaly (BS ’07, MBA ’12) and his friend Benoit Khayat.

“It all started in October 2019 when I met Benoit. He wanted to expose those leaders who were trying to ‘ride the wave’ of the reforms by positioning themselves as reformists,” Chemaly says. It was the ultimate insult and the kind of exploitative gaslighting that would deprive Lebanon’s revolutionary fires of oxygen. “All of these politicians are out there saying we’re for the people, the youth, and Benoit and I are looking at each other just infuriated.” And so, the duo decided to gamify this phenomenon.

From the start of the game, players are randomly assigned a moral-cum-political trajectory: that of the reformist leader or the corrupt politician. Everyone closes their eyes, then the corrupt players open theirs and acknowledge each other, which is meant to force those corrupt players into a collusive mindset.

Depending on your affiliation, you can choose to move through the world of politics as a mafioso business mogul, a rich drug lord’s wife, a za3eem (political boss), a journalist, an activist, a professor, a movie star, or a judge. “The corrupt character cards are marked in green, the color of sickness and money, while we see the reformers in red, the color of life and enthusiasm,” Khayat explains in a “How to Play” video on the publisher Superheated Neuron’s channel on YouTube.

The game is then divided into two phases, both of which involve political strategizing—first to capture Lebanon’s parliament, district-by-district, and second, to capture the presidency. Hence the game’s title.

Both the reformists and the corrupt begin the game with a randomized distribution of districts. And, as in the actual Lebanese parliament, different districts hold different numbers of seats and amounts of political value. To take empty districts, a player calls for an election whereby all players must vote. Alternatively, a player who holds a district adjacent to a desired one may opt to capture it by force if the player’s political holdings carry enough weight; however, the owner of the threatened district can make a play for the assaulting district if he or she can rally enough support from nearby districts.

“Ultimately, we want the game to be accessible, which is why we moved away from featuring playable characters that too closely resemble Lebanese politicians,” Chemaly says. “Corruption occurs around the world, and our potential audience is global as well.”

The first thousand copies sold out last June. “So, we reprinted another 1,500, and sales are going up.” The game of corruption, it seems, has a strong appeal.