Features

What’s in a name? SPC becomes AUB

by Barbara Rosica

Spring/Summer 2020

This year marks the centennial of an event many years in the making. On November 18, 1920, the New York State Board of Regents certified changing the corporate name of the Syrian Protestant College (SPC) to the American University of Beirut. As far back as 1901, SPC’s Board of Managers had voted to change the college’s corporate name to Syrian Protestant University, but the trustees voiced concern that resources were inadequate for a university program. They decided that the 50th anniversary of the college in 1916 would be the right moment to announce the name change, since it allowed time to accumulate the funds needed for an upgrade to university status.

As fate would have it, the Great War intervened, and the issue was put on hold until 1919. By that time, the original name suggestion of Syrian Protestant University was rejected on two counts: 1) the institution was no longer Syrian, with students now coming from all over the Near East, and 2) it was deemed inadvisable to use the term “Protestant,” as students and faculty represented nearly every religion in the Near East. The SPC faculty suggested the name used in common parlance when referring to the institution, the “American University,” and they tagged on

“of Beirut” to formalize the name. Originally, the New York State Board of Regents, under whose auspices the SPC was chartered, objected to the use of the term “American,” claiming that the SPC was located in a region where diplomatic relations might be “delicate.” The Regents also thought that the name “University of Beirut” could cause misunderstanding with the French or local education organizations in the city. The matter was finally resolved by the SPC faculty, who reaffirmed their original name choice.1

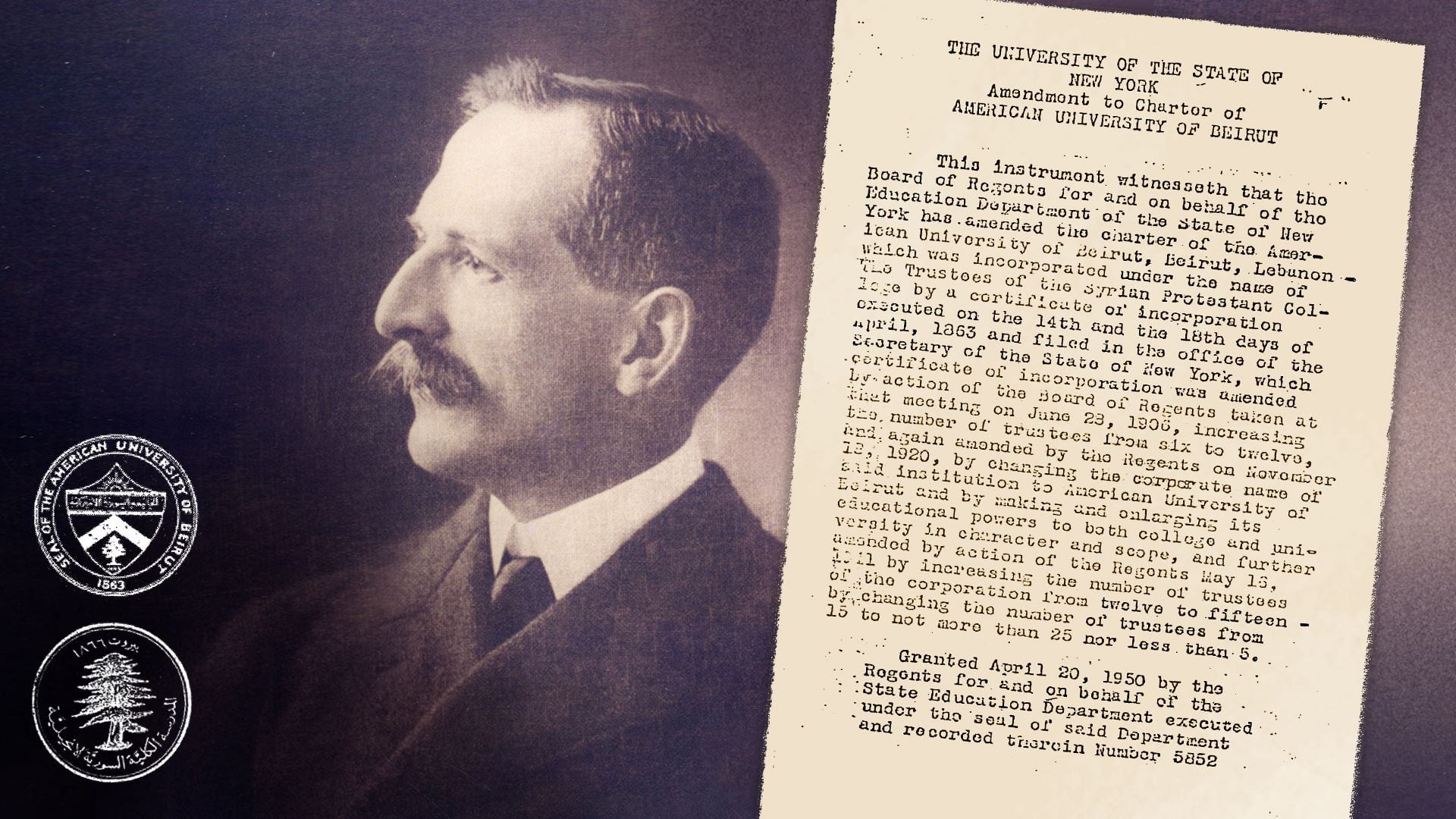

AUB President Howard S. Bliss (1903–1920) had expected to resolve the name issue in 1920, but for nearly a decade he had been immersed in a Sisyphean effort to fend off famine, war, and the chaos surrounding the decline of the Ottoman Empire. At the Paris Peace Conference, Bliss fought valiantly for Syria and Lebanon’s right of self-determination as set forth in US President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points peace plan. In a speech before the Council of Ten, Bliss made an eloquent plea for a respectful transition to independence for the peoples of the Arab region. He cautioned world leaders that “unless the Mandatory Power working under the League of Nations approaches its great task in the spirt of lofty service, her splendid opportunity to lead an aspiring people to independence will be forever lost.”2 But lost it was.

Bliss was never able to return to his only real home, Beirut. Following the Paris conference, he suffered from the debilitating effects of tuberculosis and traveled to America to convalesce at the Saranac Sanatorium in Upstate New York, where he died on May 2, 1920.

Acting President Edward F. Nickoley (1920–23) quickly picked up the mantle. He wrote in the Fifty-Fifth Annual Report to the Board of Trustees of American University of Beirut: 1920–1921, “The new name constitutes a twofold challenge; first to a broadened field of work, to the branching out onto new departments; second, and far more important, the new name imposes the obligation of producing a higher grade and better quality of work.”3 That same year, AUB granted professors institutional equality and awarded voting rights within the general faculty regardless of national origin, thus ending one facet of discrimination against Syrian professors.

Nickoley hoped that by expanding the institution’s scope from college to university, “the American University of Beirut may become a university in fact and in deed as well as in name.” Indeed it has.

1. Stephen B. L. Penrose Jr., That They May Have Life, The Story of the American University of Beirut 1866–1941 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1941), 172.

2. “Syria: Statement by Dr. Howard S. Bliss to the Versailles Peace Conference, 1919,” MainGate magazine 5, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 40

3. Betty S. Anderson, The American University of Beirut: Arab Nationalism and Liberal Education (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 53.